‘Tales From the Camera Shop’ (by John E Lewis) and ‘What Am I Bid‘ (by Tim Goldsmith) are articles that run occasionally in the pages of Tailboard. These first hand accounts of real life stories from the sales counter and the auction room floor make fascinating, and often, hilarious reading – sometimes the customer isn’t always right…

Tailboard Camera Hoard by Tim Goldsmith (originally published July 22)

Just over 20 years ago I used to write a “Collector’s Corner” section for Photoshot, (probably) the very first UK web site designed for photographers and everything photographic.

Somehow the site ended up as a photo agency and thus I was able to add yet another redundancy to my long list.

During my time with them I was asked to present a selection of cameras to the Channel 4 ‘Collector’s Lot’ TV programme. This involved me staying at a hotel near Exmouth in Devon and on the first evening an item on the restaurant menu caught my eye – ostrich steak. As the production company were paying the bill I thought I would give this a try and when the waiter served my meal he asked “Would Sir care for a steak knife for his ostrich?” I included this sentence in my “Collector’s Corner” article, thinking that would be the strangest sentence I would ever write. I was wrong.

As a long-time camera collector, then dealer and now auction consultant, I have often been to a house call where there were a lot of cameras, but I have always wished I would get the call to visit a massive horde, something like you might see on one of those TV “life reorganising” shows. On the first two days of the recent Jubilee Bank Holiday, I finally got my wish when my colleague and I visited a large house in one of the more affluent parts of the Home Counties. It turned out that the owner had been a TV cameraman in the 1960s who then went on to run his own production company. His house was so full of cameras we really didn’t know where to start. Every room was packed with piles (literally) of camera bags and boxes of cameras, lenses and accessories. Every cupboard was crammed full, one with dozens of video cameras, the next with very expensive Canon lenses, many still boxed and unused.

Even the fridge was full of film, just about every format from 35mm and 120, to 16mm cine and Polaroid sheet film. The family member who was showing us around said that they had already taken box loads of film to the dump because it was out of date! After that we (politely) asked them not to tell us what they didn’t have any more, so we could concentrate on what they actually still had.

After we had scoured the main rooms and the huge attic, we were told that there was a lot of cine equipment and other things to look at in the equally huge cellar. That’s when we were told that “In order to get to the cine cameras we will have to carefully squeeze past the Rolls Royce in the extension”.

I made a mental note to make this my new ‘strangest sentence’. Sure enough, to get to the steps down to the cellar we had to navigate round the mountains of ‘stuff’ and past said Rolls Royce which had been parked there since 1969. It had been purchased from an actor who had just retired but the new owner, being so busy with his new film editing company, never had enough time to do anything with it.

We carefully descended the incredibly narrow stairs and into the dark cellar, the one tiny bulb at the bottom of the stairway failing to shed any light anywhere other than on the top of our heads. A decent sized torch appeared and, with a little help from the lights on our smartphones, we could just make out large metal cine camera outfit cases piled up. Piled up so high in fact that we could use them as steps to get past the large lathe and a huge 1970s editing suite (how they got them down there I will never know) to the shelves right at the back. There were more Arriflex and Éclair NPR cameras down there than I have ever seen before. Although these cine camera bodies were not in the best condition, their lenses had been removed upstairs for safe keeping, including five (so far) rare Dallmeyer Super Six lenses.

Back upstairs and in one of the bathrooms I found a large pile of camera bags, each as full as they could be and, after carefully brushing off hundreds of dead wasps, I started going through the contents. Within a few minutes I had unearthed several gems, but I surprised my colleague with the last item I found. I rushed into the room where he was sorting through enough Leicas to keep anyone going for several lifetimes and exclaimed that “I have just found a brand-new Leica O Series replica at the bottom of a bath!”. Now THAT is my unbeatable favourite sentence and a reminder of the most extreme camera collection I have ever seen – so far!

And yes, if you ever order ostrich, you will need a steak knife.

What's in a name? by Tim Goldsmith (originally published in April 2020)

I have recently been cataloguing a large collection of equipment, mostly SLRs and lenses from the 1960s through to the 1990s. When the vendor sent me his list it was nearly 100 pages long, fully illustrated and in alphabetical order by manufacturer, then camera model number (or focal length in the case of all the lenses). As there were so many items on the list I knew it was going to be big task to sort them out, so I asked if he could keep things as much in order as possible when packing up the collection. When the boxes arrived, they came with a note from the vendor saying it hadn’t been possible to keep anything in order (apparently the entire house was stuffed full of cameras in every nook and cranny) so he had to box items up just as he came across them. He added that he had hand written the serial number of each item on the box and he hoped that would help. It didn’t.

This collection ran to well over eighty boxes, some of which were so heavy I could hardly lift them. As everything was totally mixed up I decided the only way forward was to get everything out, so I could get the collection into some sort of order. I made several long lines of cameras, quickly adding to each line as I came across another camera from the same maker. Nikon FA, Minolta 7000, Pentax Spotmatic, Canon FTb, Canon FA……. What? A Canon FA? Surely not. But yes, in addition to the well known Nikon FA there really was a Canon F-A.

I put this oddity to one side and went back to it a bit later, when I noticed a couple of unusual things about it. Firstly it had a removable Canon MZ motordrive fitted, but it was much slimmer than any other Canon winder I have seen and with no way of inserting batteries to power it. Guessing the small battery in the camera would not be up to operating the winder, I assumed the row of electrical connections on the front was where extra power could be picked up from. But again, they were unlike any other Canon connections I had seen. Although this camera looked to have a standard FD breech-lock lens mount, the internal mirror was much bigger that the normal version found on any other Canon SLR and it was obvious that the rear of any FD lens fitted would either foul, or possibly even break it. Also, there was a large, cylindrical extension to the viewfinder eyepiece. Looking through this eyepiece and things got even stranger, as the image could be zoomed in and out, was upside down and back-to-front.

As far as I can tell, this camera was never made available to the photo trade and doesn’t appear in any Canon range brochures, not in any of the several books on the history of Canon. It turns out the Canon F-A was part of a set-up marketed to opticians and ophthalmologists in the early 1980s and used by them for Fundus photography. This involves photographing the rear part of the eye, also known as the fundus, to check for any abnormalities. The Canon F-A was part of a dedicated Canon CF-PC1 ‘mirror’ unit which featured a Polaroid instant print system so the operator could see the resulting photograph whist the patient was still present. Although state of the art at the time, featuring a pan and tilt facility which could even produce ‘panoramic’ images of the Fundus by taking multiple exposures, this system is long since obsolete as firstly EOS autofocus and then digital imaging and scanning took over. Details of the operation of this unit are difficult to come by and the only barely decent image I could find on-line, shown here, is from www.crystalradio.cn website and here is a link to a PDF file of the operating manual https://tinyurl.com/u47berh

The above then got me thinking if there were other cameras with the same name. but from different manufacturers and the infamous Olympus M-1 v Leica M1 story popped into my head. Olympus surprised the world by launching their compact (for those days) SLR system at Photokina in 1972. But it seems that Leica were pretty miffed as their M series rangefinder system already included a camera designated as an M1. Maybe Olympus thought that no one could ever mistake their camera for a Leica and launched with that name, but they lost out and so the OM-1 was born. Depending where you look, the production numbers of the Olympus M-1 and its 50mm M-System (as opposed to the more common OM Series) lens seem to vary wildly, but in whatever numbers it was made, the Olympus M-1 was short lived and still fetches a premium over the identical OM-1.

In 1975 Minolta launched what was the first ‘proper’ autofocus film SLR system as we now know it. As was often the way, this camera was given different names when sold into different countries to help prevent the ‘grey market’ whereby a camera could be bought cheaper if purchased from a country with a much larger market. Here in the UK and throughout Europe the camera was known as the 7000 but in the USA it was marketed under the Maxxum model name. This name featured an overlapping “double XX” which didn’t impress the American oil giant, EXXON who had been using exactly the same overlapping “double XX” in their logo for some time. A certain amount of sabre rattling went on but eventually a sensible outcome meant that Minolta were allowed to market the cameras they already made, as long as the overlapping XX was dropped. Subsequent Minolta cameras and lenses were marketed using standard lettering.

In the end I suppose it is what a camera can do that matters, not what it is called. As Shakespeare put it in Romeo and Juliet, “That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” So, what’s in a name? Well, sweet FA I guess.

The Alberts - gems from an unknown collection by Tim Goldsmith

It never ceases to amaze me how many collectors are completely unknown to the wider camera collecting world and equally just how many do not know about our club. There seems to be a lot of people out there with large collections and sadly, on several occasions, I have been asked by a collector’s family to sort out and sell their cameras at auction. Whilst doing so I have often thought to myself that I would really have liked to have known this guy (I have yet to deal with a female collector) whilst he was still around.

This was the situation a while back when I was asked to value the collection of my most famous auction client to date, Douglas Gray. And if you are wondering why I call him famous when you have probably never heard of him, I think you may well of ‘heard’ him he was part of the backing group on Yellow Submarine, the animated Beatles feature film. You may also have heard of The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band? No? Then how about The Goons, The Goodies, Monty Python…..? You see, Douglas Gray (Dougie to his friends) along with brother, Tony, were The Alberts, a crazy, zany, double-act who have been acknowledged as an inspiration to all of the aforementioned, and others. In the late 1950s The Alberts were at the forefront of British satire and were a bridge between the worlds of novelty variety acts and television. In April 1962 they performed live on the opening night of BBC2 and in a rare YouTube video of part of this performance, you would swear you were watching Monty Python from almost 10 years later (it even features a giant foot). Think of The Alberts as a blend of The Crazy Gang, Flanders and Swann and The Marx Brothers and you are about half way there – bonkers, but supremely talented. However the Alberts never quite made the big time and spent much of their working lives in the then lucrative newspaper print trade. With his not inconsiderable disposable income Dougie amassed several extensive collections, including musical instruments, classic motorcycles and, unknown to his family until fairly recently, cameras.

And this is how a few weeks ago I found myself in a barn, in the middle of Norfolk, stepping over ducks, chickens and some of the nosiest geese ever, whilst on a camera hunt. It seems Dougie had run out of room in the small bungalow where I had just seen part of his collection, and was storing some more items with a friendly farmer. Although dark, there was just enough light in the small barn to pick out probably one the biggest photographic items you will ever see – a huge Hunter Penrose process camera. This was the camera Dougie used whilst working at the Daily Telegraph in Fleet Street and he rescued it when new technology made it obsolete. Although it had been in this barn for many years, the wooden parts and lens still looked to be in good condition. It was mounted on a massive ornate metal carriage and alongside were a number of plate holders of various sizes. On squeezing my way past it I was amazed to find that there was another Hunter Penrose camera behind it, although this one was slightly smaller.

Over in a cramped corner was what most people might dismiss as a load of old iron, but I always make sure I check everything so I asked Tim, the farmer who owned the barn, to pass me the first item. As soon as he picked it up I knew what it was, as I have the same camera myself, a Spanish Nemrod Siluro underwater camera (pictured, right). Unlike most other underwater cameras, this Bakelite beauty is actually little more than a waterproof housing containing the innards of a very simple 120 roll film camera. The next item from the pile was a Williamson 14A Type F117 aerial camera (pictured, top right on next page). We seemed to have gone from one extreme to another in just two cameras!

Thinking it just couldn’t get any better I was not too disappointed when the third item was the largest, dirtiest, rustiest, ugliest motorised Shackman recording camera I had ever seen. “I take it you don’t want this?” asked Tim. “Not really. But I will have this” I replied, removing the Dallmeyer Super Six lens from the front. As I had earlier collected a Shackman Mk3 Auto Camera with Dallmeyer Super Six lens from Dougie’s bungalow, I thought the world could manage without the rest of this monstrosity. After making sure the barn had been fully explored I moved down the road to a storage company where there was a shipping container waiting for my inspection.

It was so jammed full of musical instruments and cameras I could only get to the first few boxes, but I did manage to retrieve one spectacular item, a Williamson G28 gun camera (below). Intended to look and operate similar to a Lewis Mk2 machine gun, this camera was used in training to assess the progress, or not, of rear gunners. The metal parts on this example are covered in an unusual brown patina, probably caused by the grease or oil it was coated with for protection having dried out over the years. Its design and operation was similar to the earlier, and much more common, Thornton Pickard gun camera, but I did think I might have some explaining to do had I been stopped by the police on my way home with it. I decided it wasn’t a good idea to try it out on a street photography session.

Having read his full obituary in The Daily Telegraph it was obvious that Dougie was an original character. As a long-time Bonzos, Goons, Python and Marx Brothers fan it’s a shame I never got to meet him and talk about his life. We may even have got around to discussing his camera collection at some point.

* Auction prices achieved on 28th Oct 2020 were:

Nemrod Siluro £80, Williamson 14A Type F117 aerial camera £60, Dallmeyer Super Six lens £460, Shackman camera £650, Williamson G28 gun camera £3,900.

All plus buyer’s commission.

Tim Goldsmith

Print Envelopes by Tim Goldsmith (originally published in June 2020)

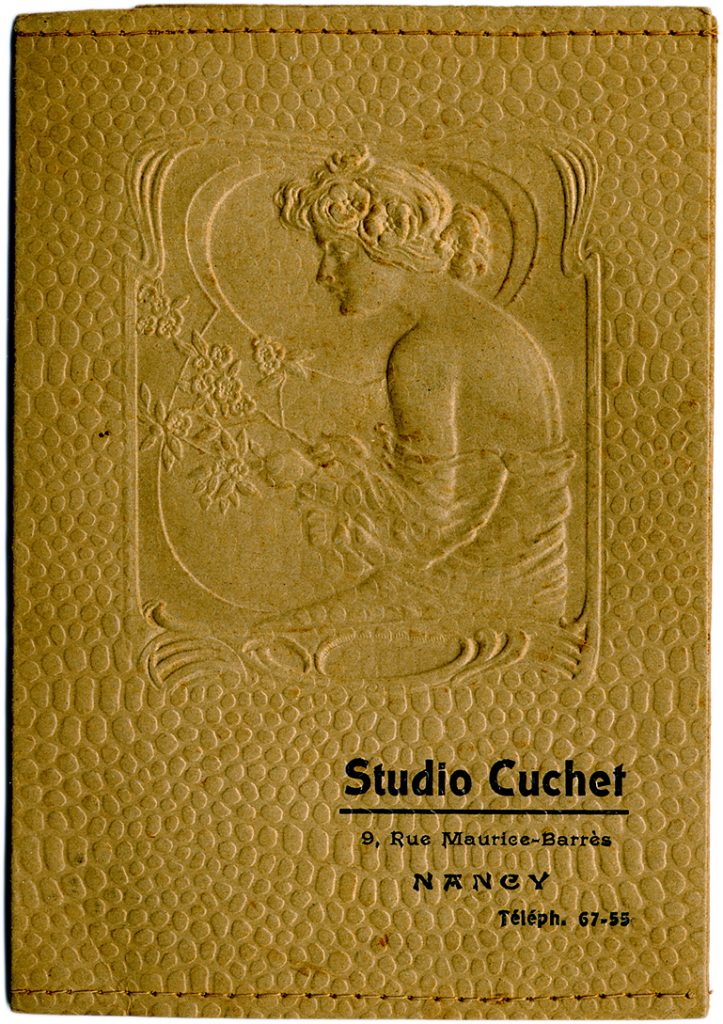

A while back I wrote about some very basic items from the Bob White Collection saying that even the most simple items can still be interesting to the collector. Sometimes even I forget that while we can all drool over exotic cameras and lenses they were really just designed as a means to an end – to produce a photograph.

I’m willing to bet that everyone reading this has at sometime taken a roll of film into a shop, or popped one in the post, to be commercially processed. Dropping off a film to be developed and then collecting it a few days later usually meant two trips to the camera shop or chemists, which provided two chances that you were at least going to buy another roll of film and hopefully for the shop, maybe something else as well.

When you collected your photographs you quickly opened the envelope and flicked through the prints to make sure they had ‘all come out’.

On returning home, a more leisurely inspection of the prints usually ensued, followed by elation or disappointment (or probably a mixture of the two). But how often did you bother to look closely at the wallet your photographs came in? Hardly ever? Never? Well, as you can see from some of the items shown here, that is a shame as there have been some very interesting examples over the years.

From the earliest days of specialist retailers, companies were keen to get their product (or at least their name) in front of you, the customer. For the retailers, the chance was that once you had collected your developed photographs, if they were good enough, you might even show them to friends and family. What better way for companies to advertise their products or services than to present your prints in a colourful envelope emblazoned with the name of the film manufacturer or the name and address of the shop that printed your masterpieces?

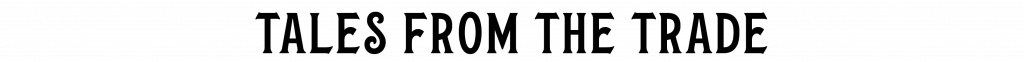

It is difficult to say precisely when the print wallet we all know first started, the earliest example in this collection is from Studio Cuchet, Nancy, France (top, right) and looks to date from the turn of the 20th century.

Post WWI as amateur photography grew ever more popular, and cheaper, things really took off and companies such as Kodak really went to town on the imagery used on their print wallets.

As with much of their advertising, even from the earliest days, Kodak print wallets nearly always featured a Kodak Girl on the front and although usually undated, a quick look at the clothes she was wearing (or in some cases not!) offered a good indication as to the date.

You could think of these envelopes as what is known in marketing speak as ‘silent salesman’ designed to remind the customer of other services that were available. A rare Woolworth’s print wallet for example recommends their roll films at (unsurprisingly) 6d each.

The most common ‘add on’ service seen on these envelopes however is probably the most obvious, the chance to order extra prints or enlargements. Often the price of these extras is clearly marked as in October 1933 when Jerome Ltd, Holloway Road, London who claimed to be “The originators of the postcard print from a small camera” where prints could be had for just 2d each. Several years later Bathes Ltd “The Camera People” in Torquay offered Post Card size enlargements at 4d each, 4 for 1/- or 6 for 1/6d. Fancy something bigger? Then how about one of their 15” x 12” prints for the princely sum of 3/6d (6/- mounted & spotted and with sepia toning for an extra 9d). Sadly it is rare to find many of these envelopes with a price list that is actually dated, but they still make fascinating reading.

Out of the 100 or so examples I have been looking through, the Bathes example features my favourite advertising slogan on the back. It sates that “…every pillar box is a receiving office for Bathes developing & printing service.”

Although I can’t date this envelope precisely I did manage to find a late 1950s photograph of the Bathes shop on-line, pictured above, which shows how big an operation it was.

But even with Google as my research friend, there is an item that has me stumped. The plain looking Vita film envelope (pictured, right) announced that “You need never buy another film…” as it offers a free replacement film with each roll developed.

On the face of it an early example of a simple marketing ploy, but inside there is a warning that “Ordinary dealers and chemists cannot successfully develop and print Vita film” and that “Vita films are ultra-rapid….”. Having never even heard of Vita film, nor being able to find anything about them on-line, I looked inside the envelope and found a small group of paper negatives but no positive prints. Any further information is welcomed.

The final stop on our tour of chemists is Bayley’s, Clacton on Sea (see picture, below). The front of their print wallet proudly announces they will enlarge your best negatives for free. Not quite such a generous offer as it first seems as the back explains you had to save up your print wallets and only once you had spent a total of 10/- on processing were you entitled to a free 6×4 print, rising to a free 10×8 print once you had spent a total of 20/- (£1). I guess this worked a bit like a supermarket loyalty scheme does today and just goes to show that in marketing, there is nothing new under the sun.

Tim Goldsmith

So Many Books, So Little Time (Frank Zappa 1940-1993) by Tim Goldsmith (originally published in February 2021)

I think that there is more about a book than just the sum of its contents. Yes, you might be able to search on-line and find the same information, you may even be able to download the text, or even a digital version of the book, but it is not the same as having the real thing in your hands. Take, for instance “McKeown’s Price Guide to Antique and Classic Cameras”. I have the last version, dated 1995/6, on my desk. Printed back in 1994 the prices mentioned could be nearly 30 years old by now so obviously way out of date, but the information the book contains is priceless. I look at mine nearly every day for some reason or another and often accidentally come across something that I wasn’t actually looking for, but which is still of interest. It might be a camera I have in my own collection or one I have recently seen or been talking about, and some little nugget of information pops off the page and into my brain. Finding things you never even knew you were looking for is all part of the experience of book ownership and falling down a Google “rabbit hole” doesn’t come close. But although some of us find buying and collecting books almost an obsession, there often seems to be a reluctance from others to pay even a sensible price for a good quality, second-hand camera book. Maybe this is down to the cheap prices found in charity shops or at car boot sales but at camera fairs I have noticed that sometimes even the most die-hard collectors are unwilling to put their hands very deep into their pockets when it comes to books.

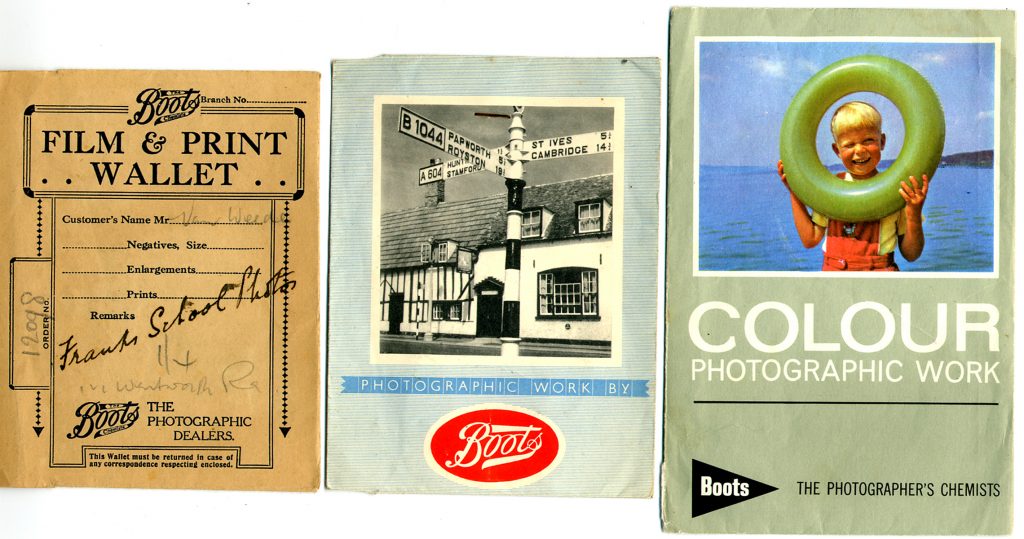

Of course there are exceptions and sometimes these can be very surprising. The aforementioned “McKeown’s Price Guide” for instance might cost you in excess of £100 for a good, hardback copy, but books don’t need to be encyclopedic in size and content to command high prices. If you are lucky enough to find a good copy of “The Ultimate Asahi Pentax Screw Mount Guide – 1952-1977” by Gerjan van Oosten, then you will need to stump up…, well I can’t even bring myself to type in this space just how much some people are asking (although as I keep telling people who say an item is on eBay for a certain price, “asking” and “getting” are not necessarily the same thing)! Published in 1999, this modest size book does exactly what it says on the cover but, being a low volume print run on a popular subject, supply never really caught up with demand and, just like cameras, that’s what drives the prices up.

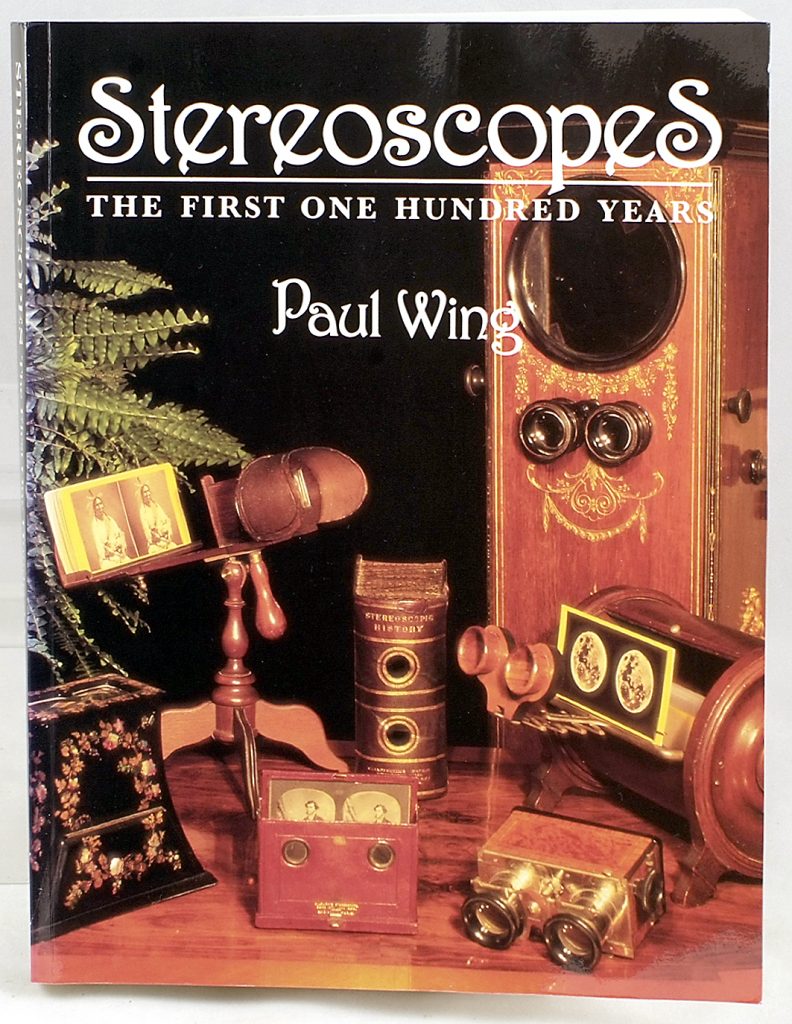

Likewise with “Stereoscopes: The First One hundred Years” by Paul Wing. Although mostly featuring items from his own collection and majoring on USA models (but with a good selection of European models), it is now almost 25 years old but is still the go-to reference book on the subject and is recommended to anyone with an interest in stereo viewers. The equivalent for stereo cards is “The World of Stereographs” by William Darrah, which lists stereo views by subject matter and includes an exhaustive list of photographers and the period when they were active. It was the same supply-and-demand story with the original edition of “Spycamera: The Minox Story” from Hove Books. I remember back in the 1990s, when they were difficult to find, selling a couple of these for almost £100 each so I was always on the lookout for copies. That is until a second edition was published, making it almost impossible to sell the original.

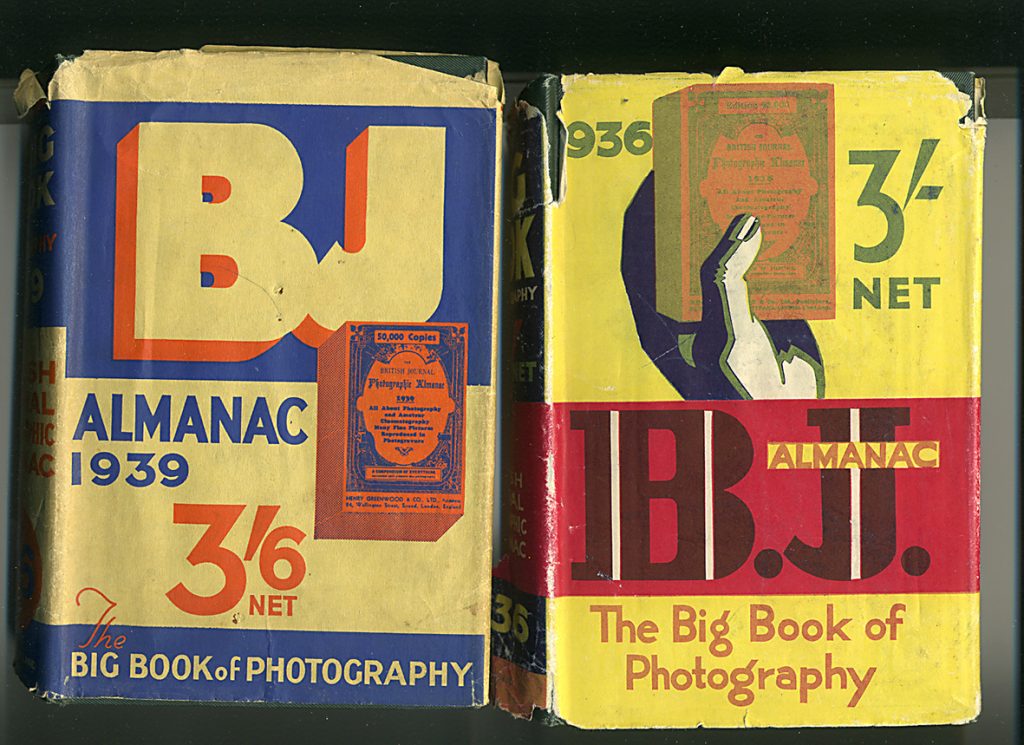

Another aspect to be wary of is, just because one particular edition in a run is sought after, it doesn’t mean they all are. If you are a fan of nature photography, you are probably aware of the “Wildlife Photographer of the Year” books. Featuring the very best nature images from around the world, and published annually for over 30 years, a few of the early Portfolios (called “Portfolios” and sequentially numbered so they didn’t have to actually have a date on the cover) are difficult to find and can attract high prices, even though editions either side of it may be available for just a few pounds. And it’s a similar story with the “British Journal Photographic Almanacs”, whose prices vary wildly. Editions from the 1950s and early 1960s are plentiful and often very cheap. Pre WWII editions are a little more difficult to find, pre WWI even more so, and so on. The further back you go, the harder they are to find and the more you are going to have to pay. If you come across one pre-1895, just buy it, almost regardless of the cost as it is almost certainly going to be better than leaving your money in the bank. Just make sure it still has all the advertising pages intact. On the subject of “British Journal Photographic Almanacs”, some club members recently helped with the indexing on-line of the range from 1900 onwards

(https://stage.pccgb.net/the-bj-index-project/).

This is going to be a very useful resource and one I’m sure we will all make use of at some time. This project prompted me to successfully seek out BJP Almanac copies for my next auction, but I was in for a surprise as three of the BJP Almanacs that came in still had original dust jackets, which I had not seen before. On asking around via club Zoom meetings and the two club email groups I frequent, we did manage to come up with two more examples with dust jackets in members’ collections, plus the report of one more in an Australian collection. The two volumes I have with their jackets, 1936 and 1939 after which date any sort of paper was in short supply so I don’t suppose BJP dust jackets continued after the war. Even more surprising was that one of the other examples found by a club member was also from 1939, but with slightly different colours, so now I have something else to look out for. Still, I often say that you can’t have too many books – and you certainly can’t have too many photography or camera books.

Tim Goldsmith

Advertising One’s Wares by Tim Goldsmith (originally published December 2021)

There is a famous quote from George Orwell (1903 – 1950) that says “Advertising is the rattling of a stick inside a swill bucket”. Whilst that may be a little harsh, I do get his point. Most advertising these days, especially TV advertising, seems to be either dumbed right down to the lowest common denominator, or is little more than a really bad, pun filled jingle. Even worse is when a TV ad appropriates a classic pop song at random and tries to project a ‘cool’ image for their product.

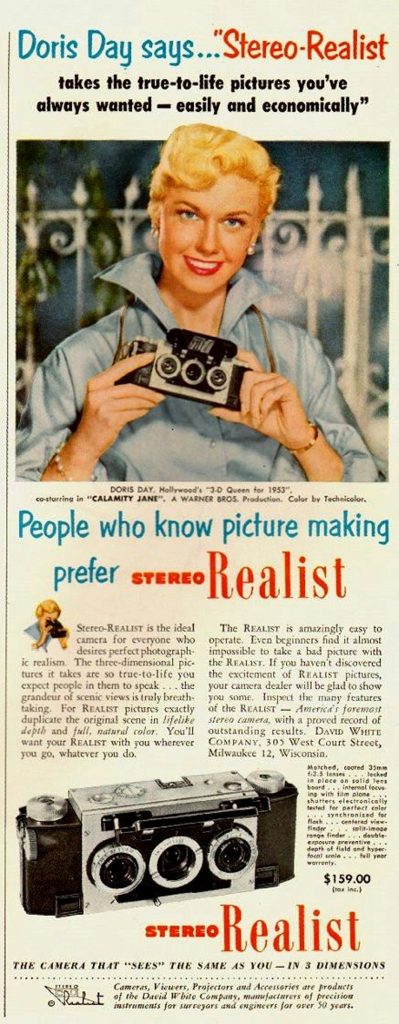

Luckily, a lot of photographic advertising in print over the years hasn’t been anywhere near as bad. In the 1970s and 1980s we had David Bailey, Koo Stark and others continuing their TV campaigns for the Olympus Trip and Olympus MJU cameras in magazine advertisements. Back in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Sawyers in the USA had no less a star than Henry Fonda advertising View Master. Go back another generation or more and post WWII the David White Company used a whole galaxy of superstars to advertise their Stereo Realist cameras. These included Joan Crawford, Bob Hope, Doris Day (who also advertised Bolex cine cameras) and Gregory Peck, to name but a few.

But probably the most often seen people in camera and film advertising are those whose names are not actually known, in particular the dozens of “Kodak Girls” the company used in their advertising. First introduced in 1901, the Kodak Girl featured in many magazine advertisements post WWI but it wasn’t until the 1960s that she really took off – literally, as life-size bikini-clad cardboard ‘standees’ could be seen outside many a photographic shop. It comes as no surprise that even within living memory, no company ever missed the opportunity of using ‘pin-up’ girls in any form of advertising, but in these more aware times much of this type of imagery is luckily on the way out. But at least not all Kodak standees were of girls, nor were they all life-size. Actor Edward Woodwood, famous for his roles in The Wicker Man and on TV as Callan, apparently had “3 seconds to spare” to show off his Instamatic 100 in a 1960’s counter-top standee.

Moving away from people in adverts, at a local antique fair recently I found a 10” x 8” card advert for Ilford film processing which could stand on a counter-top or be hung in the shop window. This simple but effective item features a clock face with movable hands and a cut-out section showing a rotating list of days of the week. Without even troubling the shop staff, the customer could tell at a glance when their pictures would be ready if they took them in – a proper “silent salesman”.

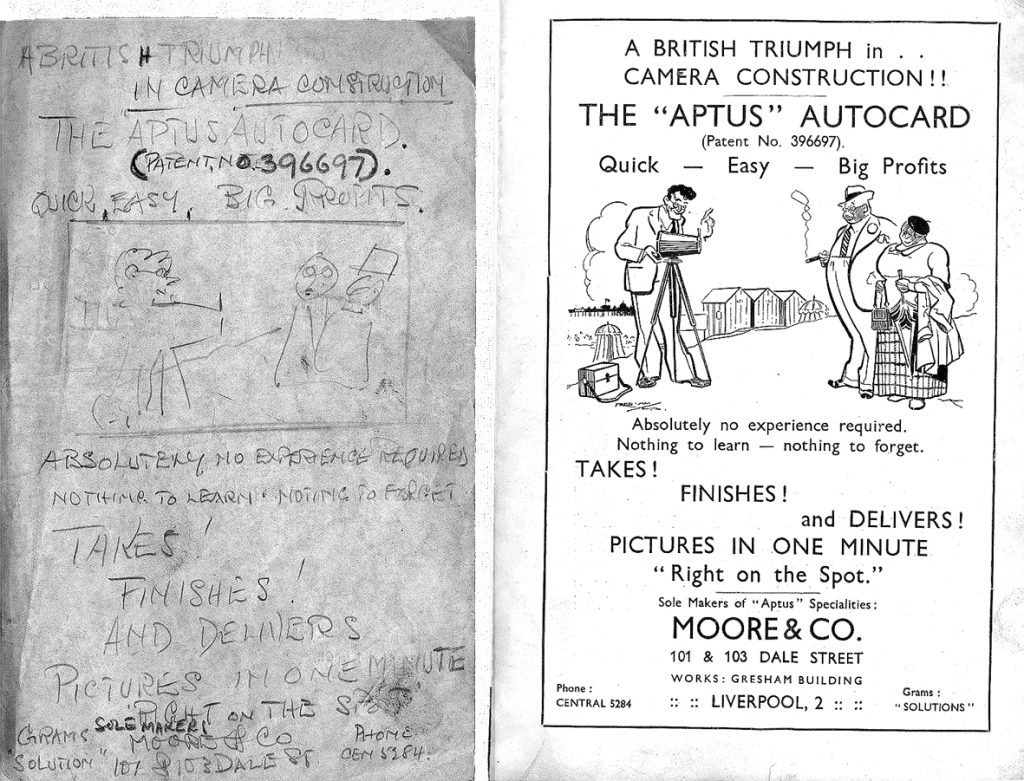

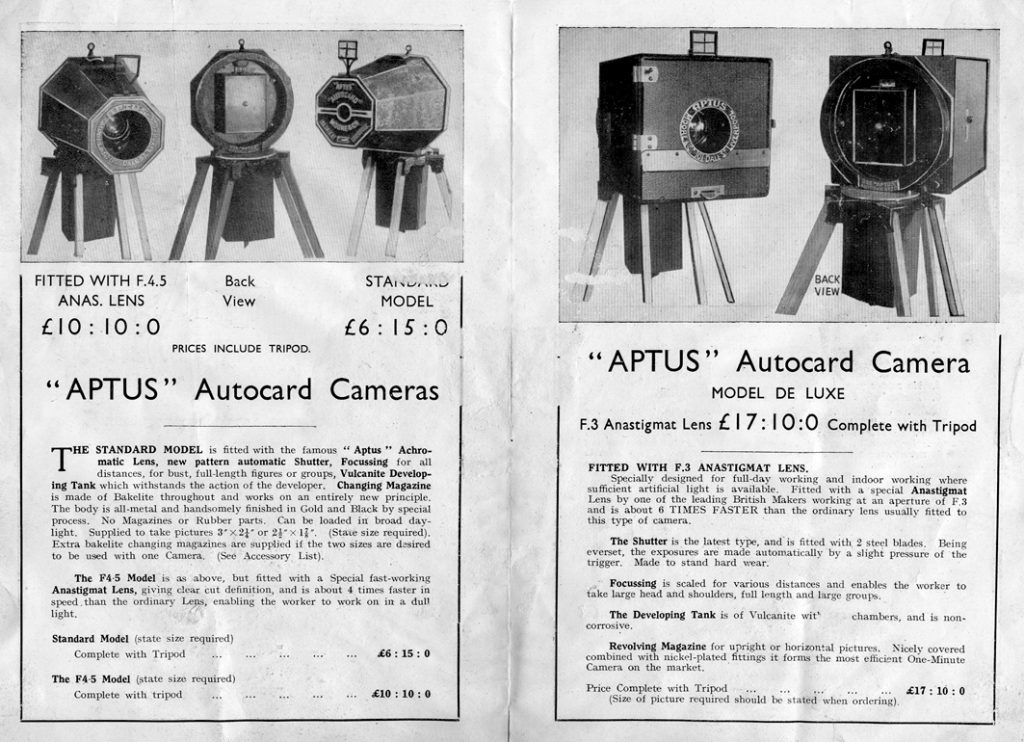

By its very nature, most early point-of-sale material was ephemeral and not much of it survives, and what never survives is the actual artwork used to create the ads in the first place. But incredibly at a camera fair a while back I came across exactly that on the stall right next to mine. Post WWI the Aptus “While-You-Wait” Ferrotype cameras were very popular, right through to the late 1930s. Along the way the company introduced the Autocard version for producing (almost) instant prints which were popular with beach photographers or those at places were day-trippers could be found. These cameras are uncommon today and you will probably have to look long and hard to find an original instruction book, let alone any advertising material. And here is the (almost) miraculous thing, through this little collection you can follow the whole thought process of the manufacturer. It starts with a handwritten sheet, folded to make four pages, on which a rough layout has been scribbled. It shows the position of a cartoon style image of the camera in use, with the relevant text around it. The inside and back pages have just a few brief points to be expanded on in what would turn out to be the finished advert. Next comes a set of four small typewritten sheets which contain the first draft of the text to be used. These sheets have been hand corrected and annotated, ready to be typeset. Then comes a group of photographs of Aptus cameras which would later be retouched and added where required. If all this wasn’t rare enough, we also have the actual finished artworks, complete with the pasted-on photographs that were sent to the printers, both of which are dated 8/6/34. Unique doesn’t even cover it!

And finally on the subject of advertising, I’m sure our esteemed editor will be pleased to know that his favourite Ilford sun-bathing guy seems to have found himself a new friend! [Esteemed Editor – I am delighted, wouldn’t it be nice to reunite them?]

Smoking out the customers - by John E Lewis

One of our regular customers was a pipe smoker, although what pleasure he got from it is hard to understand. On every visit he used to meticulously fill the bowl with tobacco, strike a match, and suck the mouthpiece loudly amid an unbelievable combination of flame and smoke. Once the beast was alight, he’d cough furiously until his eyes watered, and then wipe them dry with a large white handkerchief before the whole ensemble settled down into a more rhythmic puffing.

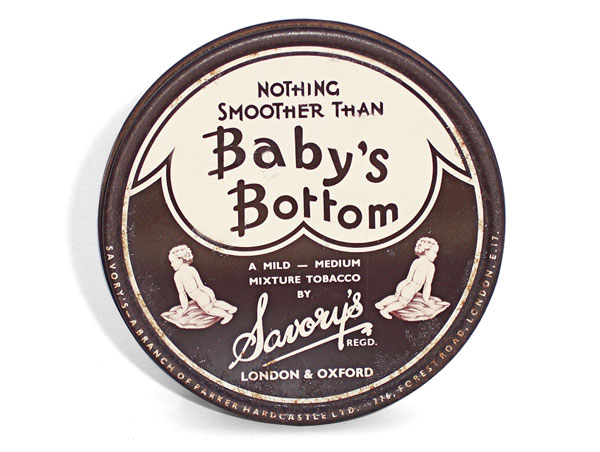

Always smartly dressed, this middle aged man named Luther ran a very successful menswear business, which often made me wonder if any garments purchased from his establishment would permanently reek of tobacco smoke. Luther was also a very good photographer – a Rollei man – and had been a loyal member of the local camera club for many years. A fellow member, Harry Evans, often joined us on the sales team during holidays and busy periods. He was a real gem, very knowledgeable on all aspects of exposure and darkroom work, and being a senior school teacher he was superb at explaining the intricacies of photography to our customers. Harry had recently become a pipe smoker after his wife had suggested it was far healthier than his beloved ciggies. Like all converts he’d made a serious study of the various tobaccos that were available, and was amused to find that one brand was called ‘Baby’s Bottom’. Truly, that’s not a wind up; check it out on the web.

On a Saturday morning shortly before Christmas, Harry had been brought in to deal with the expected rush, and that was a wise decision. Around mid-morning, five customers were being served by the sales staff, and about another eight were waiting their turn, including a pair of very gentile looking elderly ladies who I had not seen before.

Harry couldn’t contain his laughter, and nor could I, plus the other waiting customers who were all male. But I’ve often wondered how much Luther’s witty remark really cost us in hard cash. We never saw those two ladies again.

John E Lewis

A taxing time (originally published in 2007) - by John E Lewis

On nearly everything we buy the government takes a whopping 17.5% in Value Added Tax (now it’s 20%!). That’s not an insignificant sum, but for once it’s no good us harping back to ‘the good old days’. Before VAT we had Purchase Tax (PT) and in reality it was far worse, especially for photographers.

In the immediate post-war years purchase tax on some luxury goods was as high as 90%. Cameras and photographic equipment were considered to be luxury goods, but the chancellor never imposed the maximum, which was rather generous of him. These dreadful rates of purchase tax came in just prior to 1948 and remained for several years.

To give some idea of how it affected the average amateur photographer at that time, lets assume you wanted to buy an Agifold camera, a modest tripod, plus a Gnome enlarger and masking frame.The camera would have cost £16 9s 8d (£16.48) of which £4 19s 8d (£4.48) was purchase tax and thetripod retailed at £3 4s 6d (£3.23) the PT being 19/6d (97p). The enlarger was £25 16s (£25.06) of which£7.16 (£7.06) was PT, with the masking frame at £1.13 (£1.06) including PT of 10/- (50p). In today’s money that’s a total retail price of £45.83 plus purchase tax of £13.01.

Nowadays the VAT on these items would be £8.02, a saving of £4.99 against the Purchase Tax. One must also remember that in those post-war years many men earned £10 to £12 a week, a far cry from the current average UK wage of £447 per week. (If you can believe that figure!) So the poor fellow buying the outfit might have shelled out more than his weekly wage just to pay the purchase tax.Some items of equipment were exempt from PT. Enlargers for negative sizes 7 x 5 inches and above were considered ‘professional’ while those up to 5 x 4 inches were not. There was no PT on contact printers,studio lighting stands and reflectors. Projection equipment, either still or cine, was also exempt as it was widely used in ‘education’ and one can only wonder if the chancellor ever realised the huge quantities being sold to amateurs. We loved selling projectors as they were more profitable than cameras. For example, if a new projector retailed at £30 we would get a trade discount of 33.3 % so with no tax we made a clear profit of £10. But with a camera selling at £30 we only made £7.00.

Do you remember some of those absurd rules when VAT first came in? Such as if you bought fish and chips and ate them in the street they were VAT free, while eating them in the chippie would deem them to be a restaurant meal and liable for tax. Only governments have the brains to dream up such rubbish and they were no different with purchase tax. If our commercial photography department supplied a mounted print in a frame there was no PT on the frame. But if the customer took the print away and wanted it framed a week later, the frame then became taxable as it was no longer a part of the original commission.As for amateur equipment, then let’s take cine ‘bar lights’. You may remember those two or four lamp units which were fastened to the cine camera’s tripod socket with a standard quarter Whitworth knurled screw. If we bought the lights with the screw attached they were ‘a camera accessory’ as the unit could be fastened to the cine camera, and that made them liable for PT. Ordering them undrilled and without the screw they couldn’t be attached and were therefore free of PT making them £1.3.11d (£1.19p) cheaper. Fifty years on I can now tell you how my boss saved our cine customers money. We always ordered the lights without the screw fitted. When a customer came in to buy a set we told them about the stupid PT regulations. Naturally they thought it was a rip off, so we explained that the unit would be supplied undrilled, with a separate screw costing two shillings and threepence (about 11p). All they had to do was drill and tap a hole to make the light fully operational. For those unable to do it we’d drill and tap the hole as ‘a favour’ after closing time. Was it legal? Probably not. My boss saw it this way. If the customer couldn’t drill the hole themselves they’d probably seek help from a friend or neighbour. So why shouldn’t he be that good neighbour. After all, no charge was being levied, so the £1.3.11d was not being pocketed as extra profit. That’s also a reminder of the most important part of photographic retailing in those days – service. If there was a similar situation today with VAT and a lighting unit for a digital video camera, what are the chances of finding a shop on any High Street that would be willing to do such a favour for a customer.

Answers on the back of postage stamp please!

John E Lewis

All At Sea - by John E Lewis

Jack was the owner of a couple of hairdressing salons, and he told me that he and his wife were going on a Mediterranean cruise in a month’s time. He’d had thoughts about making a film of the trip, but having only used simple stills cameras in the past he was a bit worried that a cine camera might be technically challenging.

His timing was perfect. Bell & Howell had just launched the Autoset (1958), the first fully automatic 8mm cine camera. I’d hardly finished demonstrating one before Jack pulled out a wad of notes to buy the camera plus a roll of Kodachrome to try it out.

Ten days later he came in with his newly exposed film and I laced it onto a projector. For a first effort it was excellent. The camera had taken care of focus and exposure, and Jack’s shots were steady – unlike most new cinematographers he’d avoided over-panning. Delighted with his effort he bought a dozen rolls of Kodachrome ready for the cruise.

As he was visiting hot countries I suggested that after exposure he didn’t replace the original black tape around the edge of the film cans, but bind it crossways instead. Not only would it allow the can to ‘breathe’, but it would also denote which rolls have been exposed and which are unexposed should they get mixed up. Jack agreed that was a good idea and I wished him bon voyage.

One morning a few weeks later Jack phoned me. ”That B cine camera you sold me is a load of rubbish,” he barked, “It’s ruined my holiday.” Thinking there must have been a serious mechanical problem, I asked when it had stopped working, but he interjected with, “Oh it runs OK but my films are all over the place. Some have nothing on them at all, they’re all black, and on others there are up to three images. I mean, I’ve got shots of the Mediterranean Sea with traffic on it – B cars and lorries in amongst the ships. This is a total disaster; I’ve a good mind to demand my money back.” I asked him to bring the camera and films along for examination and within an hour he and his wife had arrived.

We all went into the projection room and I screened the rolls with images on them, and then checked the blank ones on a rewinder. Sure enough there were treble images on two rolls, double on three, one was normal, and the rest had never been through the camera at all.

John E Lewis

Awash with Stardom - by John E Lewis

A couple accompanied by their two year-old daughter were interested in buying a cine camera. Like most proud parents they wanted to film their daughter’s childhood, and their budget was just £30.

After showing them a selection of 8mm cameras, the husband decided on a single-speed German Cima-D8 with a fixed focus f/2.8 lens which was just sixpence within budget. As I started to make out the bill he pointed to a similar model in the showcase and asked what it was. I explained that it was another version of the camera with four filming speeds plus a f/1.9 focusing lens, but it cost £10 more. Pondering for a moment he commented that it might make sense to go for the extra features.

His wife, who had been rather jovial up to now, put on a very pained expression and said loudly, “The cheaper camera will take the same pictures, so why waste money. You know I need a new washing machine.” I started to get vibes that family tensions might be brewing. “I think I’ll take the dearer one,” said the husband, only to be cut short by his spouse shouting, “It’s a ridiculous waste of money,” to which he calmly replied, “It’s alright, I know what I’m doing.” Instantly the dear woman’s face reddened with rage and heading for the door she yelled, “my bloody washing machine’s clapped out and all you want to do is waste good money.” The door was slammed with such force that expensive cameras rocked precariously on their glass shelves, and several display cards tumbled down. “Sorry about that,” he said with great embarrassment, so I asked if he wanted a moment to go outside and speak to his wife. He didn’t, and promptly purchased the better camera and a roll of Kodachrome.

About ten days later the family returned; at least they were still together. Hubby had shot the first roll of film and asked if I could show it to them. After lacing the projector I switched the lamp on to see shots of their daughter riding her tricycle down the garden path. Then mother appeared hanging out the washing, which, I assumed, must have been done in her ‘clapped out’ machine. “Oh look at me,” she said excitedly, “I never thought I’d be a film star.” Her nylon overall and the profusion of hair curlers were hardly Marilyn Monroe, but no matter. The lady was overjoyed at seeing herself on the silver screen, and got even more excited with every frame.

Much to my surprise, ‘ the film star’ came in two days later and asked for another roll of Kodachrome. “I’ve managed to save some money out of the housekeeping, and this is a surprise for my husband,” she said, quickly adding, “if he comes in you wont say anything, will you.” I assured her of discretion, amazed at this dramatic change of attitude compared to our first meeting.

The couple became regular customers and soon bought a new projector. An unexpected promotion also meant that hubby forked out for that long awaited washing machine. Sadly her screen test in Hollywood came to nothing. Too many curlers, I suppose.

John E Lewis