digital dodger

The Digital Dodger is a regular feature from the pages of Tailboard magazine. Each article focuses on a particular aspect of combining a digital camera body with ‘classic’ lenses, lens adapters (new and home made) and assorted accessories that can be used to great effect.

You can jump to each article using the buttons below

Mixing Old and New – what can they do?

A look at using legacy lenses on digital cameras

Whether you like it or not, you cannot escape the fact that digital cameras have taken over the world of photography. Be it a modest mobile phone or a high-end digital SLR all are capable of recording images of great clarity and colour with a minimum of user input.

What digital users may miss is the tactile and creative satisfaction of manually focussing with a ‘proper’ lens, setting the aperture with a ring and the shutter speed on a dial, as film users were used to.

However, the days of film are not over as many people are visiting or revisiting the medium. Sales of film, new film manufacturers appearing, and the rise in price of second hand film cameras support this. The days of carrying a couple of SLRs and half a dozen lenses in a back- breaking/neck-straining hold-all may well have passed (and will not be missed!) but the sight of someone with a lm camera at events, tourist attractions and on the streets is now more common than it was just a few years ago.

Film does have its problems – is it fresh, is it a good batch, will I expose it correctly, is the camera light tight, will I or someone else mess up the processing, will it get lost in the post? Problems which digital does not have.

If you are a collector or enthusiast photographer with lots of older or, as they are known, ‘legacy’ lenses how do you use them without the restrictions of film? They may have sentimental value or have a special purpose – micro, macro, soft focus, extreme telephoto, mirror, tilt/shift for example.

It is well known that adapters have been available for mainstream digital SLRs for many years but these often have use limitations due to different brand’s flange – film/sensor distance (register) if infinity focus needs to be maintained.

For those who wanted to use legacy lenses on digital cameras the big breakthrough came in 2008 when Panasonic introduced its G1 mirrorless or CSC (Compact System Camera) camera with a 19.25mm flange to sensor distance.

With such a shallow body depth, adapters were soon available to use Leica rangefinder, cine C mount and all of the major 35mm SLR manufacturers lenses that were not electronic.

Accurate focusing is aided by variable magnification of a chosen part of the image. Many cameras now have an electronic split image rangefinder or focus peaking which highlights high contrast edges with a choice of colour and intensity to help judge the point of correct focus.

Some mirrorless formats have come and gone but the recent mainstream models can be classified into 3 groups:

Micro Four Thirds (M4/3) Sensor size 17.3 x 13mm, made by Olympus and Panasonic. They share the same lens mount. With a 1:2 crop factor, an adapted 50mm lens would be equivalent to a 100mm lens in 35mm terms.

APS-C format. Sensor size is around 23.6 x 15.7mm (there are slight variations between manufacturers). No shared lens mounts. Manufacturers such as Canon M, Fuji X, Sony E, Leica L They have a 1.5/1.6 Crop factor, eg 50mm lens equals 75/80mm in 35mm terms.

3. Full Frame. 24 x 36mm sensor size as standard 35mm. Examples: Sony FE, Nikon Z, Canon RF, Leica M. Lenses made for 35mm cameras clearly have no crop factor but be aware with all formats that wide angle lenses may disappoint – at the edges in particular. This is because of the way the light hits the sensor rather than hitting the film.

Certainly at wider apertures most lenses perform better at the centre than the edge, often because smaller sensors are just using that central ‘sweet spot’ to record an image. The crop factor means smaller sensors are less useful with wider angle lenses but increase the effective focal length of longer lenses.

Our recent NW Group meeting had Russian equipment as its theme. I took pictures with several readily available legacy standard lenses on a digital camera as part of a practical comparison. Without going into great detail, there were variations between individual lenses as expected but when well stopped down all the lenses produced an acceptable image. Some examples are shown here.

To sumarise this brief over view, it is clear that adapted legacy lenses do not have the clinical contrast and sharpness of modern lenses. They don’t need it. With carefully chosen subjects and conditions the user can get more actively involved in creating a satisfying, acceptable photograph without the need of expensive modern equipment. Surely that is something to interest many collectors?

Mixing Old & New – A quartet from Leitz

Around 10 or so years ago, at the time when digital was just established as the clear winner in the big debate of film vs digital, I was converted but still kept a foot in the film camp. I was in a photographic society, competing in a postal portfolio which only allowed the use of Leica screw mount cameras and lenses. I enjoyed making prints in the darkroom but eventually it became impractical and I reluctantly resigned from the group. I hung on to my Leica 3g and 4 lenses just in case I went back to it.

Eventually I sold the 3g body as it was not being used. By this time the APSC size sensor mirrorless cameras were on the market with the 1.5 crop factor which made using old lenses more viable than the 2 x crop factor Micro 4/3 camera I had been using until then.

My favourite Leica screw mount lens by far is the later version of the six element, 35mm Summaron. The f2.8 version is superior, but I had sold my “M” fit version reluctantly some years before. The 1957 vintage, E39 filter size f3.5 L39 model is compact, well laid out and handles well thanks to the focussing tab and click stop aperture. Prone to flaring, I have adapted an old Johnsons lens hood using additional card baffles in an effort to reduce its effects. It also allows for easier aperture changing than the official Leitz IROOA clip-on hood does.

The results are sharp and pleasant, on my Fuji it has the effect similar to a 50mm standard lens. One of the drawbacks with using rangefinder lenses is the rather less useful closest focussing distance of 3 feet 4 inches. Most SLR lenses focus to half that distance but are not so compact.

The earlier more compact A36 filter mount version of the lens performs just as well optically but does not handle quite so well due to the rotating mount.

The next lens in the set is a 1937 50mm f2 Summar. Another six element lens, I had heard many disparaging remarks about it, mostly concerning scratched soft glass on the front elements. Mine is a clean version and, considering its age, it performs very well. It is quite compact when collapsed and is centrally sharp at f2. Being uncoated I keep a modified (with internal black flocking) modern 34mm screw-in lens hood on it. Stopped down to f8 the lens is fine for most purposes.

Clearly digital images can be dramatically altered in post processing, eg in Photoshop. Having less contrast, older lenses can often be given a little boost by using in-camera settings at the time of taking. For this, I sometimes use the Velvia film simulation mode in the Fuji, the effect being visible in the digital viewfinder.

Sometimes seen in rows on dealers’ shelves, the four element 9cm f4 Elmar was the classic Leica portrait lens. Mine is a 1959 E39 filter mount version. It is not a “wow” lens but was made for many years with good reason. It provides useable image quality, especially around the mid range apertures. Some can be found quite cheaply.

I find the standard code 12575 clip-on reversible hood works fine (and also fits some 135mm lenses). The lens head, containing the optics, unscrews for use on bellows or mounting in vintage Leica close up devices. It also provides alternative methods of mounting the lens onto mirrorless or DSLR cameras but involves delving into expensive, complex and scarce vintage Leitz adapters. All best avoided if you like to keep things simple.

The lens head is also removable on my last lens – the four element 135mm f4 Elmar. Dating from 1960 it takes the same reversible 12575 clip-on hood as the 90mm, has the luxury of click stop apertures, a tripod mount and a long focussing throw. It is the lightest of the Leica rangefinder 135mm lenses and, although it does not get used frequently, its performance does not disappoint. It is generally a highly regarded lens.

I have used the earlier 135mm 4.5 Hektor lens and, whilst not as sharp, I found that it gave pleasant acceptable images, especially in monochrome. Much like the Summar it is one of those lenses where it is worth ignoring what others say and try one yourself to see if you like the results.

Leica lenses have always enjoyed a reputation for quality, even these older models. The 50mm Summar, 90mm Elmar and 135mm Elmar can often be found at very reasonable prices. The 35mm f3.5 Summaron is usually dearer and for the f2.8 version you will need to have very deep pockets.

There are many cheaper lenses available that do a similar and sometimes a better job. However these lenses have a build quality and a feel to them, and whether you can understand it or not, for me and many others, there is just something special about a lens which has come out of the Leica factory.

Taken with 1960 Leitz 135mm Elmar

Taken with 1960 Leitz 135mm Elmar

Mixing Old & New – Braun Paxette lenses

The Braun Paxette range of cameras from the 1950/60s has long been a favourite amongst camera collectors. They are cheap, fairly available, have a range of body styles and many lenses (McKeown’s lists 28 lenses, not including the Katagon shown here) by different manufacturers.

The interchangeable lenses, both coupled and uncoupled with the rangefinder, mostly used a Leica type 39mm screw fitting. The catch was that they have a longer register and are therefore are not interchangeable with the Leica cameras.

The Wallace Heaton Blue Book for 1959/60 lists a “distance ring”, price 19s 1d, to allow Paxette lenses to be used on Leica (without rangefinder coupling) and Periflex cameras.

Like many, over the years, I have had a fleeting interest with Paxettes and somehow, somewhere I acquired what I believe to be a Wallace Heaton distance ring. It is just an L39 extension tube 15.2mm long and allows the Paxette lenses to focus to infinity on a Leica camera or a mirrorless digital camera with a Leica L39 adapter fitted.

The original distance rings must be quite rare. Very similar and not quite so rare, often found at camera fairs, are Leitz extension tubes, code named DOORX and 14020. They (and some other brands around the same size) can be placed between the lens and camera adapter to allow the lens to focus at useable distances.

The Paxette lenses, being of their time, were built to a price. Many of the standard 45/50mm models were 3 elements, being generally acceptably sharp in the centre but rapidly diffuse in an artistic manner towards the edges (even on a crop sensor digital camera).

Because of their heritage and design features some lenses handle better on a digital camera than others. Click stops are useful but not found on all the lenses. I have tried several of the standard lenses over the years and have found none to be striking but most are acceptable, especially stopped down. Some are quite attractive and look good on the camera.

If you have a collection/selection of Paxette lenses I urge you to try them on a mirrorless digital camera. The results can often be pleasing in

colour and, given the right subject, even more so in black and white, be it shot in-camera or converted from a colour image afterwards.

Using Cine lenses

2008 saw the introduction of the first mirrorless interchangeable lens digital camera, the Panasonic G1. With the aid of simple adapters it was possible to use the lenses from many earlier SLR and rangefinder cameras. This system also brought new life to a range of cine camera lenses, often of high quality, which had remained largely dormant and forgotten having been made obsolete by the arrival of the video camera in the early 1980’s.

The most useful of them, with a 25.4mm diameter screw thread were first introduced in 1926 and are known as the ‘C mount’. They became the standard lens mount for many 16mm cine cameras. The lens had a register of 17.526mm and the frame size was 10.26 x 7.49mm. The Micro 4/3 frame size is 17.3 x 13mm and the flange to sensor register distance is 19.25mm. By comparing these figures three things are clear:

That any ‘C mount’ lens adapter that is to retain infinity focus has to be recessed into the lens throat of the camera.

The cine lens coverage onto the larger digital format will often result in vignetting, particularly with standard and wide angle lenses. This can often be used creatively.

When buying a ‘C mount’ to M4/3 adapter it is advisable to look for one with the largest possible diameter recess. This will allow a wider choice as some ‘C mount’ lenses are quite bulky and may not physically fit or seat fully on the adapter.

As well as 16mm cine lenses, some CCTV lenses use the same thread, but not always the same register and in general are not as good quality or as well made as 16mm cine lenses. They often have unmarked aperture rings and no focussing scales. Instead they may have locking screws on both if intended to be used at a fixed location and distance.

16mm “C” mount cine lenses have been made by most of the major lens manufacturers, the standard lens focal length being 25mm (50mm equivalent in Micro 4/3). Being of their time, many of them have chrome or similar finishes with finely engraved scales which are often difficult to see. They often suffer from being stiff due to dried lubricants. When video cameras replaced most 16mm film camera the lenses were plentiful and cheap because very few people could find a use for them. Their usability on mirrorless digital cameras drove prices up.

Other cine lenses that are often seen are ‘D mount’ lenses made for interchangeable lens 8mm cine cameras. These are like miniature ‘C mount’ lenses and have a standardised 15.88mm diameter screw thread. Again, they were made by many manufacturers but their practical use these days is limited.

A later but now discontinued range of mirrorless digital cameras, the Pentax “Q” system, had a small sensor and shorter (9.2mm) register. Because of this it was able to make use of ‘D mount’ lenses and adapters are still available on the internet.

The only use I have found for ‘D mount’ lenses is to reverse them and adapt them to any digital camera to use them for macro work. I have a 13mm f1.8 Kern-Paillard Yvar lens reverse mounted on to an M42 T2 mount using a filter mount, card and glue. This allows fairly easy use on most digital cameras with suitable adapters. A stable camera mount, patience and experimentation are needed for reasonable results to be achieved.

Another non ‘C mount’ 16mm camera lens I have is a USA made Wollensak Type-V, 13/8 inch (35mm) f3.5 from a USAF WWII aircraft gun camera. This has an aperture scale with a simple exposure guide to accommodate weather conditions and camera frame rates. There is no focussing ring, but mounting it in a salvaged CCTV lens mount solved that problem. The lens performs surprisingly well.

Of the ‘C mount’ lenses I have tried over the years I have only kept hold of one, a 25mm f1.9 French Som Berthiot Cinor “B”. Not exciting or expensive, it is sharp enough in the centre and the field curvature gives the edges of the frame a pleasant glow. Additionally, it vignettes increasingly as it is stopped down. (Turning the camera to shoot in square format cures that).

Micro 4/3 is the longest established mirrorless camera format. Other, now discontinued, cameras had smaller formats, eg the Pentax “Q” and Nikon 1 systems. Adapters for cine and CCTV lenses are available for them.

Some more recent APSC and full frame cameras that have shorter lens register distances could also be used with cine lenses but due to lens coverage serious vignetting could occur, making it impractical except with possibly some of the longer focal length lenses.

It is always a good feeling to make a pleasant image using an old lens. Using cine lenses in this way, it is the creative photographer who may get more satisfaction than one trying to make a purely record photograph.

Right: What appears to be a modified 36mm f2.8 Steinheil Cassarit ‘D mount’ lens, reverse mounted onto a Nikon “F” flange.

Found like this at a camera fair. Shot with a 50mm f1.8 Olympus OM lens

Periflex lenses in use today

Much has been written about the unusual British designed and built Periflex camera system of the 1950’s and 1960’s. This is not another article about the Periflex system but is about using the Periflex lenses on modern digital cameras. The early cameras used the Leica 39mm thread and had the same 28.8mm register as the Leica cameras of the same period. This means that the lenses will readily work on a modern digital mirrorless camera equipment with a standard readily available Leica adapter, be it either an L39 screw or an M bayonet adapter fitted with a separate L39 screw adapter ring.

The first Periflex item I acquired was a Focussing Screen Adapter. This is simply a tube with a female 39mm thread at one end and a focussing screen at the other which was set to the Leica/Periflex register. It was designed as a close-up focussing aid. Its main use for me (and the chaps I worked with at the time) was for checking the thread and focus of obscure threaded lenses found when trawling around camera fairs.

The more often found Periflex lenses themselves are, in my experience, nicely made, compact and light weight. They generally look good and have clearly marked scales. In my examples the aperture ring moves easily but the focussing can be stiff and both rings are similar so need to be used carefully. They are still easy enough to use a modern mirrorless camera.

A useful feature of some of the lenses is that the focussing ring turns for more than 360° which gives them a good close focussing ability. For example my 35mm f/3.5 Retro-Lumax lens will focus down to 6” and 45mm f/3.5 Lumax to 12 inches from the lens front.

I also have the 100mm f/4 Lumar which, like the other two, conveniently takes the same 42 mm push-on lens accessories. They were all introduced in 1957. Strangely, they all turn to focus in the same direction but the aperture scale of the 35mm Retro-Lumax turns in the opposite direction to the other two.

Fairly recently I acquired a cosmetically good but non-working 2nd version, black Periflex I body complete with a coated standard 3 element 50mm f/3.5 Lumar lens. This dates from 1954 and the compact design of the lens is completely different from the later lenses.

Using these lenses on my usual 16mp APS-C sensor Fuji XT-1 digital camera is straightforward, the adapters fits easily, exposure can be manual or automatic. Focus is achieved using the magnified image with the lens set at full aperture. The 1.5 crop factor of the camera means for example that a 50mm lens will be equal to a 75mm lens in 35mm full frame terms.

My main interest is to see if these older lenses can produce an image which is usable and acceptable today. I am not really that concerned with many of the usual lens flaws, such as lack of contrast or chromatic aberration, these things are easily corrected in computer software.

Sharpness can be of great concern to many, I am of the view that a lens does not always need to be pin sharp in order to produce a good photograph. Some would argue that some modern lenses can be too sharp anyway. Much depends on the intention and ability of the photographer. I leave others to do forensic testing.

To try out the lenses I used each with different subjects shooting each with the aperture wide open, at f/8 and f/16. I expected them to be soft wide open and they were. At f/8, a more likely to be used aperture, things had improved. At f/16 they all produced some useable images despite my fear that diffraction would be softening the image. I felt that the 4 element 45mm Lumax, which at f/11 produced the best images of the four, being very similar to other makers lenses from the period. The 35mm, despite having a deep scratch on the front element performed well when stopped down, as did the 50mm Lumar. My least favourite was the 100mm Lumar, despite being more generally soft did produce a nice still life. It’s a matter of taste and choosing your subject.

I had acquired these lenses over a number of years out of curiosity, and because they were British (well, mostly). For anyone who owns Periflex lenses and a digital mirrorless camera I would encourage you to give them a try and perhaps show your results to a wider audience through Tailboard or PW.

To summarise, for me Periflex lenses are pleasant and easy enough to use and they can produce an acceptable result although they may not be my first choice to take out on a photo shoot – but if I found a 35mm f/1.9 or an 85mm f/1.5 Periflex lens, that would be a different matter.

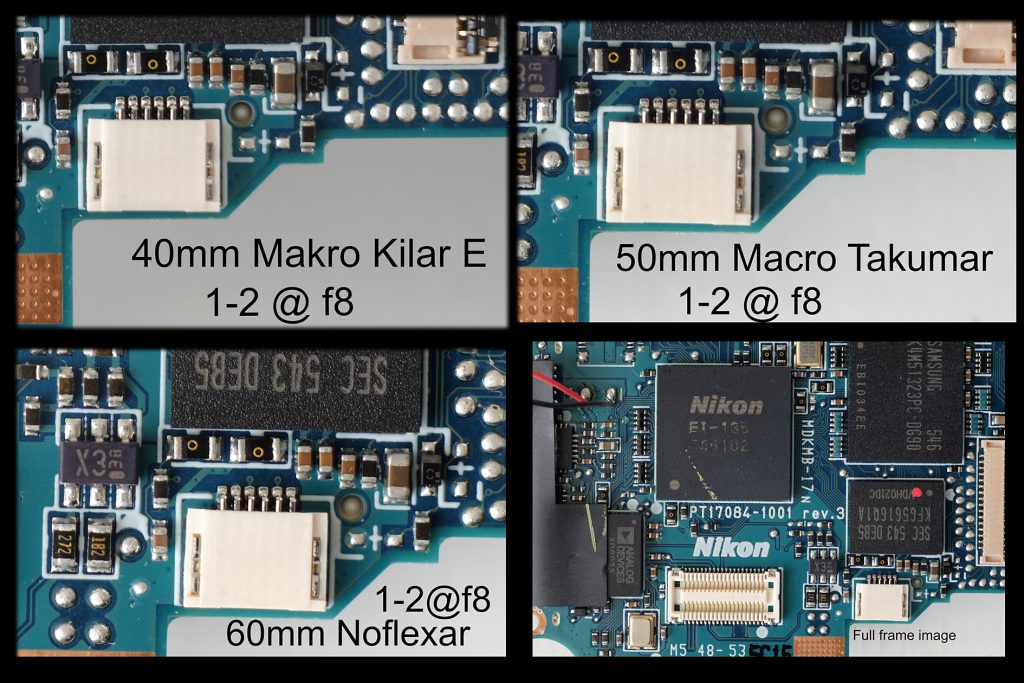

Heritage macro lenses – 40, 50 & 60mm

Introduced in 1955 the 40mm f3.5 Kilfitt Makro Kilar is generally regarded as the world’s first dedicated macro lens for 35mm SLR cameras (note the unusual spelling of Makro). It is a 4 element Tessar type design, and was made in two different types. “E” or Extension which focussed from infinity to half life size and “D” Double Extension which focussed to life size. In common with many later macro lenses the front element is deeply recessed. It was made in Liechtenstein in a variety of camera mounts, the most frequently seen being M42, Exakta and Alpa. Compact and lightweight, with a simple and positive preset iris ring this lens has great appeal when adapted to a modern digital camera.

In 1958 the lens was updated to an f2.8 aperture, the “E” and “D” types being retained. My own lens is an “E” version of this type in Exakta mount. A word of caution here; I have two different Fuji-Exakata adapters, one is a combination of two commercial adapters and the other home made. With either type my Kilar struggles to focus to infinity. I have seen mention of this issue on some internet forums so, clearly, my lens is not alone. Can any club members throw any more light on this? The same adapters with other Exakta fit lenses (CZ Jena and Meyer) will focus to infinity.

In use, wide open, the lens is fairly soft and lacks contrast but is quite acceptable when stopped down to the f8-16 range. The focal length and preset iris does not lend itself to photographing insects for instance but for general static record shots it is fine and makes satisfactory images.

The next lens is the Pentax 50mm f4 Macro Takumar. This lens has the familiar 42mm screw thread mount and was current from 1964-66. Another compact and attractive lens, this is also a 4 element Tessar type design and has a two-ring, clearly marked, manual preset iris system. Later variations of the lens had automatic diaphragms. The aperture scale has additional colour coded settings which when used with the colour coded reproduction size scale on the focussing ring simplifies the exposure compensation adjustment required as one focuses closer. Most cameras of that time would not have had the luxury of TTL metering. Compact as the lens is, it has a double helical focus ring and will focus down to 1-1 reproduction.

Accepting the limitations of the pre-set iris, in use the lens is pleasant and quick enough to use. It has the solid feel, sharpness and quality of Pentax lenses of that period. Even today the macro and distance results are very acceptable for most purposes. For me, the quality and easy adaptability of its M42 mount makes this lens a ‘keeper’.

The final lens of the trio is a bit of a mystery and any help about its background would be appreciated. There is very little of substance that I can find on the internet. It is marked “Novoflex-Macro-Noflexar 1:4/60” on the front bezel and “Made in W. Germany” on the rear. It could easily be confused for an enlarger lens as it has a Leica 39mm lens mount. The iris is click-stopped at full stops between f4 and f22, and there is a 40.5mm front filter thread.

Novoflex are known for their fine engineering of adapters and other photographic accessories, including bellows and close up equipment. However their lenses were out-sourced. It seems likely that mine is a re-badged Staeble Katagon and was made in the late 1960’s or early ’70’s (there are more references to a 60mm f4.5 Katagon but few for the f4).

Made for use on bellows and possibly for dedicated slide copying I have adapted the lens for use on my Fuji using an e-Bay purchased ‘Kecay’ M42 17-31mm helical focussing mount coupled with a home-made short Fuji to M42 adapter. For the macro images I held the lens at the infinity focus point and added a 30mm M42 extension tube. With this useful helical mount the lens focuses from infinity to about 18 inches. They are also available in other lengths and fittings.

Results were pleasantly surprising and like the others when stopped down there was good contrast and sharpness to a point where the lens seems to me to be the same standard as the Pentax.

To summarise, like any older lenses, these are of their time and cannot be expected to compete with modern equivalents.

In practical hands-on use today, for me, the Takumar leads the way followed by the Noflexar and then the older Kilar. Not as convenient to use as a modern lens, these older lenses, especially when stopped down and with basic digital post-processing are capable of giving acceptable results for most purposes.

The bonus is that you may already have one or something similar in your collection and when using it adapted to your digital camera you can get acceptable results (eg useful for Zoom meetings) whilst getting that tangible satisfaction that comes with using these classic lenses.